| . | Terre Di Nessuno |

| back | | Index | 0 | 1 | 2 | 3

| 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 | 8

| 9 | 10 | 11 | 12 | Español | |

|

Enclaves of

intersection

Ana Vega-Toscano The borders dividing the

different artistic disciplines lost their firmness throughout the 20th

century, acquiring a flexibility broad enough to permit the appearance

of numerous territories of intersection, fields of lands fertilised by

the most innovative productions, of wide and proven transcendence in

the artistic course of the century now past. To this was joined the

emergence of new means of expression, often linked to new technologies

which are rapid generators of new idioms and of innovative strategies,

as elements that enrich this world of intermediate spaces and their

drama of aesthetic interbreeding.

Music has been freed of its bonds in its communion with these experiences, which witnessed their first and decisive steps thanks to the historic avant-gardes. However, it was the years of the second half of the century that witnessed the most rigorous consequences of this trend towards the dissolving of the classical categories of art. Soon a line of relationship was established on this musical path1, beginning with the pioneering works of Erik Satie, Marcel Duchamp and the Futurists, to be followed by John Cage and then by the artists making up that broad conglomerate known as Fluxus2. But one can obviously look further back to keep detecting attitudes anticipating the future musicians, such as Rossini and his irresistible Péchés de vieilles, to cite only one well-known example. The interrelation of artistic expressions developed in space and time has contributed to a much more free exchange of strategies than in ages past3, creating spaces of intersection which have achieved pre-eminence in the art of our time. Obviously such spaces of fusion and mixing of art have always existed, especially on the stage, whether in sacred or profane rituals, but intersection in itself was seen only as a marginal by-product, whilst today it is the centre of attention. In this context, Dick Higgins coined a term to describe that new category of art whose place of expression lies between the different media: Intermedia4. In fact, it describes an artistic category that had already taken on real forms, although they had not been categorised as such, and theses are the backbone of the joint works made by Concha Jerez and José Iges since 1989, and particularly the works discussed in this article -those that our artists have described as Conciertos Intermedia [Intermedia Concerts]5.

They

find themselves immersed in a whole series of works which Jerez and

Iges call Media Interferences: With these we aim to work from the

interior of the conventions of these media (radio, city traffic,

museum, concert hall) to evoke non-routine readings that question their

use6. The crossroads of society and the environment thus is presented

in an artistic reality whose unexpected messages cause estrangement and

disorientation, by-products of some of those no-man’s lands to which on

this occasion we are summoned by Iges and Jerez.

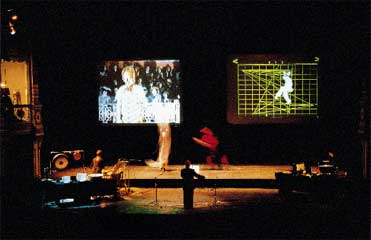

The

concert as a media reality, both in its acceptance as a musical-stage

performance event and as an arrangement of different elements, is thus

presented as an ideal interference point, using all the media supplied

by the artistic development of the 20th century, and especially the

ones spawned in those enclaves of intersection which for a long time

were lands to be colonised. Installations, radio art, all the varieties

of acoustic and electro-acoustic music, as well as text in its diverse

possibilities as sound art, video-art strategies, and, of course, such

essential concepts for the art of our time as action and performance,

conjugated with traditional stage devices such as lighting, are the

elements employed in the intermedia concerts, making them not only

objects to be dealt with, but also constituent gestures.

For

the celebration of the ritual of the concert they conquer new stage

spaces, which on more than one occasion have a decisive influence on

the work itself. This is the case of Despedida que no despide. Requiem

escénico en memoria de Agustín Millares Sall7, made

specifically for the building housing the Centro Atlántico de

Arte Moderno in Las Palmas de Gran Canaria, and also of Música

de circo para una catedral8, conceived expressly for the unique

Cultural Tank space in Tenerife, which the artists regard as a

container, a space for making visual, gestural and, above all, acoustic

interventions. In both instances the buildings become another element

of the works, also suggesting the possibility of concert and

installation. Hence, Despedida que no despide offers the chance to

attend a concrete and unrepeatable stage ritual, officiated in the

auditory and visual installation created for this space, and at the

same time it left open the possibility of the personal and intimate

path of enjoyment of the installation in itself. As regards the second

work mentioned, the artists themselves define their intermedia concert

on this occasion as an installed concert, given the preponderance of

that concept as a pillar of its conception.

Also

the re-use of materials at a more cellular level, which are transformed

into stylistic features of our artists’ work: an example would be the

sound of music boxes, of certain lithophones, or of some live-music

electronic instruments, to cite only the audio aspects of the works,

but in the same way some narrative resources, such as the montage of

statements and testimonies of different people interviewed11,

transforming into an artistic element one of the most typical

strategies of radio journalism. The use of elements that are purely

musical, in the most classical sense of the term, can be variable,

ranging from the use of the literal quote, made into a device for

disorientation or de-contextualisation, to the important presence of

fragments of improvisation, used as a tissue of sound, in many

instances in a dialogue or juxtaposition with electro-acoustic media.

Among the latter, a wide panoply of figures with fragments of social

reality or with sound objects, some of them transformed almost into the

artists’ sound fetishes. For this structure, Iges and Jerez have a

small number of performers/accomplices whom they deploy cleverly as a

true human factor in the narrative structure12. 1 Thus it was expressed by René Block in Música Fluxus: el acontecimiento cotidiano [Fluxus Music: The Everyday Event], a lecture given on 12th December, 1994 at the Fundació Tàpies in Barcelona, in the framework of the exhibition entitled En l’esperit de Fluxus. Published in: http://www.uclm.es/artesonoro/olobofluxus.html 2 In fact a genuine tide of aesthetic liberation, impermeable to delimitation and classification, and hence to the strict adherence to a term, although the name “Fluxus”, chosen by the man who wanted to be its spiritual mentor, Georges Maciunas, reflects better than any other that idea of movement and liberty which characterises these artists. 3 Illuminating in this respect is the title El espacio del sonido. El tiempo de la mirada [The Space of Sound. The Time of a Look], given to the exhibition curated by José Iges in 1999 at the Koldo Mitxelena in San Sebastián. 4 Higgins, a member of Fluxus, formulated his neologism in the mid-1960’s. 5 It is a term not previously used as such, even though there were manifestations which really evinced its characteristics, such as José Iges’ Vostell y la música, a lecture given at the Museo Vostell Malpartida on 27th November, 1998. Published by the Asociación de Amigos del Museo Vostell Malpartida, 1999. Iges points out as such Vostell´s Fluxus concerts. 6 Concha Jerez and José Iges: Préstame 88. Concierto Intermedia. Programme notes to the concert in the series Encuentros. Música y Tecnología. Centro de Difusión de la música Contemporánea. Museo Nacional Centro de Arte Reina Sofía, 19th May, 1996. 7 Despedida que no despide. Réquiem escénico en memoria de Agustín Millares Sall [Goodbye that is not a Goodbye; Stage Requiem in Memory of Agustín Millares Sal]. Authors: Esperanza Abad, José Iges, Concha Jerez. Performed on 31st May and 1st and 3rd June, 1990 in the Centro Atlántico de Arte Moderno in Las Palmas de Gran Canaria. Information and articles, as well as technical details, in the programme-catalogue published for the occasion by the CAAM. 8 Música de circo para una catedral [Circus Music for a Cathedral]. Intermedia concert staged on 27th and 28th April, 2001 in a former oil storage tank known as the Espacio cultural El Tanque, in Santa Cruz de Tenerife. 9 Spaces which, although not forming a part of the work, are always reflected in some way in it, seeking in this way the adaptation to each stage media, with some non-essential transformation. 10 El diario de Jonás [Jonah’s Diary]. Concha Jerez/José Iges. Performed by: Belma Martín, Pilar Subirá and Pedro López. UM /Unió Musics, 1997. CD-32. 11 This is an important resource in the structure of Préstame 88 and Despedida que no despide. 12 In this aspect we might mention the names of Pedro López, Belma Martín, Pilar Subirá or the author of this article. 13 In co-authorship with Esperanza Abad, a key figure in Spanish music in the second half of the 20th century, from her privileged position at the intersection between music and theatre, who has worked with José Iges in such projects as Ritual or Para la galería. 14 TransParade, debuted on 24th October, 2001, at the Teatro Cervantes in Málaga. 15 José Iges himself alludes to this special position and consideration of the piano in Fluxus y la música: un vasto territorio por explorar [Fluxus and Music, a Vast Territory to be Explored], in an article in the catalogue of Fluxfilms, published by MNCARS, Madrid, 2002. |