| . | Terre Di Nessuno |

| back | | Index | 0 | 1 | 2 | 3

| 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 | 8

| 9 | 10 | 11 | 12 | Español | |

|

Intermedia

performances by Concha Jerez and José Iges

Gloria Picazo One of the most significant

aspects of the performance, which since the 1970’s has taken its place

amongst other forms of artistic expression, has been the attempt by

artists and critics to define this form in a manner that can express

its complexity. However, two aspects have imposed themselves throughout

the 20th century since the initial experiments by the Futurists and

Dadaists. In first place there was the need to incorporate life

experience –the moment lived, the time that passes– into the artistic

discourse itself. In second place, and as a consequence of this, came

the obligatory participation of a public that until then had been able

to approach a work of art without being questioned directly by the

artist. Concha Jerez made her first incursions into body art in 1984,

and she continues to work in this artistic idiom, which she has made to

evolve from her initial actions, performances and ceremonies to her

current intermedia performances and concerts, staged since 1990 in

collaboration with José Iges.

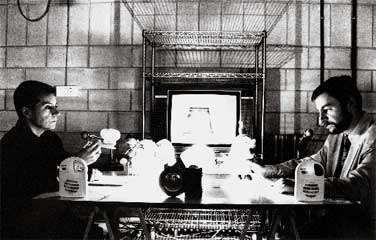

Their performance work in partnership over the past decade has served to show together, in a single space and a limited time, some of the aspects that make up their respective artistic careers, Concha Jerez’ in the visual arts and José Iges’ in the art of music and sound. Though they work together on common projects, they each defend their freedom to understand performance from different points of view, offering parallel paths that converge in a unique space in which the visual and auditory frame a given space-time situation in which the performance takes place. Concha Jerez refers to her performances as a series of individual actions, carried out though mechanical and hieratic movements, closely related to her pieces and installations, and which we daresay represent the placing before the spectator of the very processes of conception of her work. For Concha Jerez, the performance is an act of being which is totally removed from what we might understand as a theatrical action. The latter, however, is the position defended by José Iges and is based on an act of representation. He thinks up a character and interprets it. He represents himself as an author, as for example in Nick en La Habana [Nick in Havana] (Barcelona, 1995) in which he appeared disguised as an emigrant wearing an ironic cap. Consequently, his contributions to the ensemble of the proposal tend to be more theatrical, textual, almost pataphysical, as he himself hints, and they become something like an act of prestidigitation with the technological devices that have taken on increasing importance in the conception of his works. Concha Jerez was nourished by the experience of Fluxus and the intense activity in the 1970’s of that group of body artists, while José Iges has gradually formulated his principles relating to the performance in literature and theatre. For Concha Jerez, performances are constructed from tasks that are carried out before the public, in keeping with a pre-established scheme, but without excessively strict patterns. Their intermedia performances are quite different from their intermedia concerts. In the latter there is a score and performers who may be themselves, although other musicians and performers may take part.

Taking up again one of the crucial aspects of the art of performance –its expression before a live audience, which often wonders whether to react as it were attending the theatre, or whether to keep a greater distance, as if visiting an exhibition– Concha Jerez says she is not concerned by the presence of spectators. The artist tries to create a strong tension between herself and the actions she conducts with her objects, and which are often situated in the context of installations, as was the case with her performance entitled The Scenary (Cologne, 1999) which took place in the framework of her exhibition Shadows of the Scenary at the Schüppenhauer gallery. There she performed a series of actions for the public, calling them rites, which made up the process of creating a work, which previously had been shown only as an end result, such as the action of burning a series of papers, placing the remains in glass vessels and situating them in her installations. However, the artist says she experiences a feeling of great solitude during her performances and consequently the attitude she adopts is one of self-protection, when in fact she is exposing herself. The outcome of all this is that Concha Jerez carefully keeps her distance from the public, and this matches with the practice of José Iges, although he rejects the idea of ritual and advocates the utilisation of the public by conveying the sensation that the performer is very close, when in fact his actions and readings are intended to create an abyss between himself and the public.

These linked actions that will lead to the realisation of a performance normally take place, as we have mentioned, in the context of an installation made by Concha Jerez, or a space conceived specifically for her, and in the latter instance what prevails is more the need to create a situation, a particular circumstance, than a physical space defined artistically by a series of elements, and thus sound become an unsurpassable resource for enveloping and lending unity to the narrativity previously established by the artists.Estas acciones encadenadas que conducirán a la realización de una performance suelen tener lugar, como ya hemos señalado, en el contexto de una instalación de Concha Jerez o bien en un espacio pensado específicamente para ella, y en este último caso, lo que prevalece es más la necesidad de crear una situación, una determinada circunstancia, que un espacio físico definido artísticamente por una serie de elementos y para ello el sonido se convierte en un recurso inmejorable para acoger y dar unidad a la narratividad previamente establecida por los artistas.

One

of the fundamental aspects governing any performance is the

introduction of the time factor as a primary component which will not

only help to establish its development, but at the same time will be

crucial for the response of the public, which, as we already pointed

out, finds itself obliged to adhere to some particular patterns of

behaviour which are not normally followed in other types of

manifestations of the visual arts. Many artists have said that their

interest in the performance is rooted in the fact of being able to

share a particular time with the public and that everything occurs in

real time. This meaningful fact has meant that today some basic

concepts of the performance are revised and retaken by those young

artists interested in promoting what has been called an aesthetics of

the event, for which a fragment of reality becomes an aesthetic

experience thanks to the role of the artists as mediator. But also

contributing to this revision has been the use of new technologies,

from video to net-art, which has meant that representation and

temporalisation are becoming inseparable factors.

The

incisive criticism used to portray some of the social and political

discourses in their performances likewise evince the need to turn to

objects and actions charged with large doses of irony. Objects such as

those dismembered Barbies that Concha Jerez places in a bowl to mix

them as if they were ingredients of a salad, and actions like the

supposedly respectful attitude both artists display when the anthems of

different nations are heard. |